Could Sydney house prices reach a $1.5m point of no return?

With the availability of credit improving and interest rates declining, it is very possible Sydney could once again enter a market frenzy.

Much to the dismay of pundits, Sydney, Australia’s most populous city, often drives national housing market commentary. There are various reasons for this. One is its distorting effect on nationwide data and statistics. Another is its sensitivity to market forces such as the availability of credit. Take, for instance, the impact of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority’s (APRA) mid-2010s interventions on residential mortgage lending. The most frequently discussed was APRA’s expectation that lenders “assess home loan applications using a minimum interest rate of at least 7 percent” which purportedly reduced the borrowing capacity of some buyers by five-to-six figures overnight. This guidance and others were wound back in mid-2019, around the same time as three cuts to the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) cash rate target (75 basis points in total). It also corresponded with a federal election outcome widely believed to benefit residential property investors.

Expectations coming into 2020 were that Sydney, and Australia more broadly, were facing a year or more of strong housing price growth. Latent data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)confirmed this had already been taking place in several city and regional markets from mid-to-late 2019 when changes took effect. Alas, the coronavirus pandemic then descended upon us, inspiring a flurry of both optimistic and pessimistic assessments of the future of Australian dwelling prices and rental incomes. In the first half of 2020, the RBA made additional cuts to the cash rate target and the federal government borrowed more than $115 billion to begin funding a suite of initiatives including JobKeeper, JobSeeker and HomeBuilder. Over this time, the CoreLogic Home Property Value Index has shown month-on-month price corrections in some capital cities, however house prices are still notably higher than they were 12 months ago in every city except Perth. In other words, the late-2019 housing price upswing was of greater magnitude than pandemic-induced corrections (at least to this point).

Something that came unexpected, at least to me, was the Treasurer’s 23 September announcement to wind back the National Consumer Credit Protection Act 2009, effective April 2021. The reasoning was that responsible lending obligations (RLOs) are no longer “fit for purpose… which risks slowing our economic recovery”. It aims to reduce the red tape involved in obtaining credit for households and small businesses, which serves as one less barrier for prospective Australian home buyers obtaining a mortgage. With greater availability of credit, consumers are likely to find themselves better able to shop around for the best deal. This has the clear potential to increase competition between lenders, placing downward pressure on mortgage interest rates.

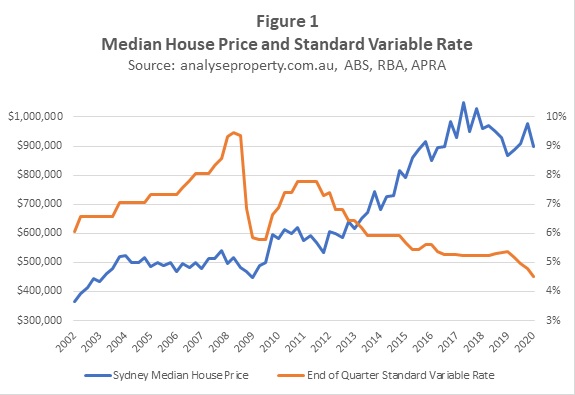

Improvements to credit availability follow a decade of progressively declining mortgage interest rates and upward trending Sydney house prices. This places Australian home buyers in a perceptively enviable position. As it stands already, mortgages have become more affordable and easier to obtain than has been the case for at least the past half-decade or so. Consider the three primary determinants of mortgage affordability: house prices, incomes and interest rates. Figure 1 below charts the last two decades of two of these: standard variable mortgage interest rates and Sydney’s median house price. You can see a negative correlation (lines going in opposite directions) between these two variables since 2011.

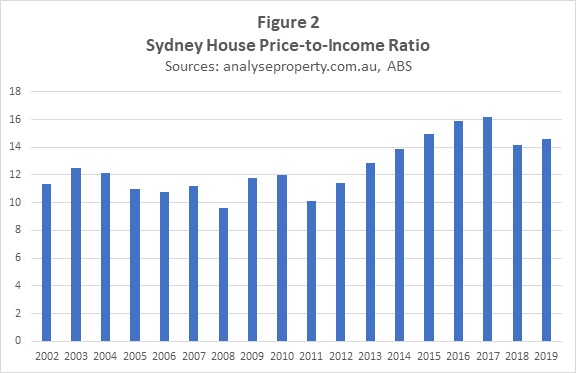

But what does this recent negative correlation say about Sydney’s property market? We can contemplate this further by looking at a more familiar statistic: the ratio of house prices to annual incomes. Figure 2 shows that the ratio of Sydney’s house price to NSW’s median personal income generally bounced between 11 and 12.5 from 2002 to 2010. By 2017, however, it had peaked at 16.193. Between 2010 and 2017, income growth had little in common with price growth. It was all about interest rates. This did not happen to other Australian cities, at least not to the same extent.

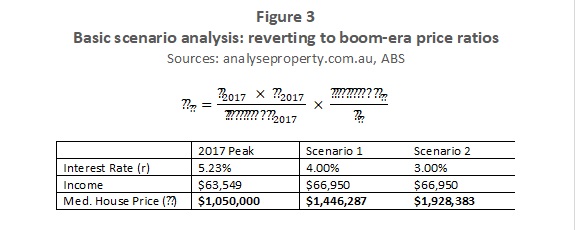

I would argue the biggest factor that stalled Sydney house price growth from 2017 was the APRA interventions discussed at the beginning of this article. Now that they’ve been relaxed, it is very possible Sydney could enter a market frenzy at equal or greater magnitude as was occurring a little over a half-decade ago. By aligning current income and interest rate ratios with those last experienced during Sydney’s 2017 peak, the implied median house price approaches and even exceeds $1.5 million (see Figure 3). With speculation that more lenders are working toward sub-2 percent interest rates, upward pressure on Sydney’s house prices could be even greater in severity.

If Sydney’s median house price reached $1.5 million, it would become more than 22 times NSW’s median personal income. If other variables don’t intervene and Sydney prices indeed approach or exceed this level in the midst of the post-pandemic recovery, homeowners could reach an intimidating point of no return. For example, borrowers would have to prove they could afford $105,000 in annual interest payments if APRA revived their serviceability calculation above 7 percent on an 80% loan-to-value ratio home. This may seem absurd, but the very idea of a median house price exceeding $1 million also seemed absurd a mere decade ago. Aside from regulatory intervention, other ways of preventing the Sydney market from running off the tracks include variables not taken into account in the above scenarios. These could be internally imposed limits to periodic credit growth by lenders (as was the case recently for investors), inability for buyers to fund deposits on runaway property prices, or coronavirus-induced influences on sentiment and borrowing capacity. But here’s the kicker: last time APRA tried to intervene in a runaway Sydney property market, it took almost three years for median house price growth to stall.

If the Sydney market (or any other Australian market) started getting out of control, I would caution would-be buyers to first contemplate how much of an interest rate increase they could afford.

Luke J. Graham, Property Analysis Australia. Luke is a property market and behavioural analyst. He is currently in the UK completing research and postgraduate study at the University of Oxford.