Negative gearing negativity on the nose

Hands up: who’s sick to death of hearing the bunch of rubbish about negative gearing from people in high places?

If some politicians and lobby groups were to be believed, negative gearing is nothing but a cash grab by greedy investors who sit around in baths full of $100 notes laughing maniacally at how the government is paying them to get rich.

What a load of codswallop!

Shelter statistics

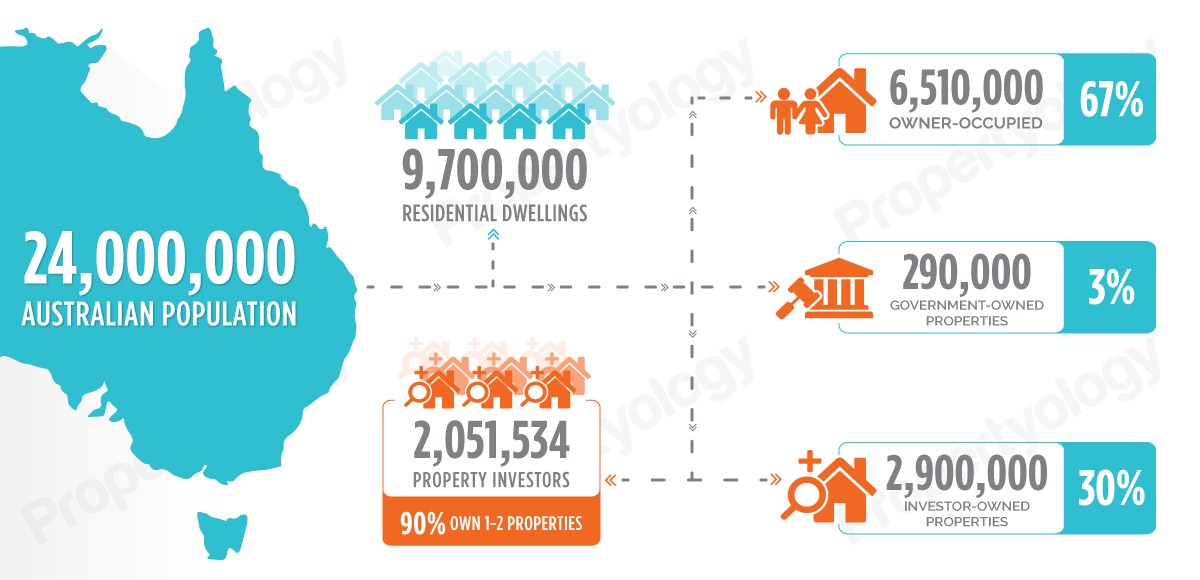

Firstly, let’s consider who provides the majority of rental accommodation in Australia.

Governments provide a mere a 2.9 per cent of dwelling stock, which is a figure that has been reducing year after year.

Why should they dip their hands in their pocket filled with taxpayer’s money to provide housing for the disadvantaged when investors are doing it?

As such, it falls to everyday Australians to fund the acquisition of shelter for others in our society – and that’s not at all to say that everyone who rents is doing so because they can’t afford to buy.

That supply by investors equates to nearly 2.9 million dwellings.

The question, of course, becomes what motivates investors to spend $300,000 to $650,000, as well as the potential risks, to put roofs over other people’s heads?

The answer is they buy properties because of the expectation that – over time – the asset increases in value and so does their financial situation.

Society wins from that, too, because it means there’s less strain on taxpayer revenue from aged pensions and that, in turn, means more funds for essential services provided by our public servants plus more infrastructure.

Time in the market costs money

For most people starting out on their initial investment journey, retirement is still a gazillion years away.

Rental income is rarely anywhere near enough to cover costs every year.

Who can afford that? Who wants to wait all of those years for a return?

The solution dates back some 80 to 100 years ago.

Back then the government had the same challenge as today, which was how does our nation fund the supply of sufficient dwellings for its growing and ageing population?

To encourage everyday Aussies to fund shelter for others, the then-government afforded them the same tax benefits that were in place for other income-producing assets such as businesses, farms, retail shops, factories, and share portfolios.

Over the years, the term “negative gearing” was adopted for investment in residential property, however, the concept is no different to tax policies for these other income-producing assets.

And while investment in myriad asset classes are eligible for negative gearing, it is residential property investors who always bear the brunt.

This was especially so at the height of Sydney’s property boom (2013–2017). Naïve commentators tried to blame investors for driving up prices.

I am far from convinced that either side of government has reflected on the importance of the decision that their predecessors made 80 to 100 years ago.

Reading headlines over recent years, it would seem that a century-old national tax policy was the root cause of property price rises in two capital cities, Sydney and Melbourne. These same naïve people failed to mention that prices actually fell in two other cities for three consecutive years (Perth and Darwin) and that four other cities recorded only modest growth.

How can a tax policy that is applicable to an entire country have such an influence on just two cities? Where did these people get their education?

The axing of negative gearing was firmly on the political agenda before and (sigh) still after the 2016 Federal Election, but no one could correctly forecast the potential impact on property prices if it was diluted or scrapped.

And while negative benefit “handouts” are often hot media topics, no one seems to mention the amount of tax revenue that all levels of government receive from investors.

In fact, while residential property investors wrote $3.719 billion off their taxable income in the 2013/14 financial year, CoreLogic estimates that investors paid capital gains tax on $51.2 billion of profits made from dwelling resales over the 2015 calendar year, which contributed to the $45 billion in property-related tax revenue collected by the state and local governments.

That's right – $45 billion in property-related tax revenue.

Markets move in mysterious ways

There are dozens of factors that influence fluctuations in property prices with tax being just one of them.

It’s the sum of all these many factors that matter, which means there is no way to calculate what impact the scrapping of negative gearing would have.

To those who say it will make housing more affordable for first homebuyers, I ask how?

For starters, negative gearing has no bearing on a person’s financial discipline to save a deposit.

And to those who try to justify it by claiming housing will become cheaper, how does falling property values benefit the 70 per cent of Australian households who’ve already done the hard yards to save a deposit and buy a home?

Personally, I don’t care whether negative gearing stays or goes. People will always need to invest and Australian real estate will always be the most popular vehicle.

However, it’s only fair that any change must be applicable to ALL income-producing assets, which means that authorities must first thoroughly assess the broader implications on our financial system as well as society in general.

Failing to do so would be gross negligence!